Over the past 25 years, the ozone hole that forms over Antarctica each spring has begun to shrink.

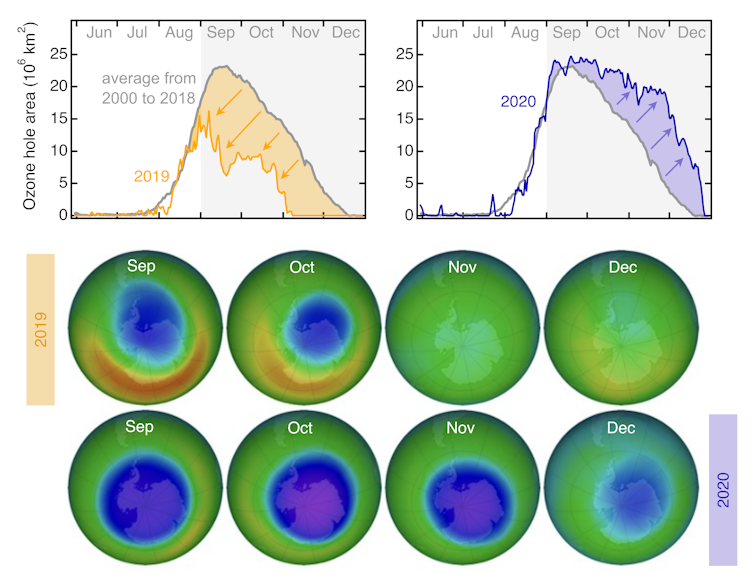

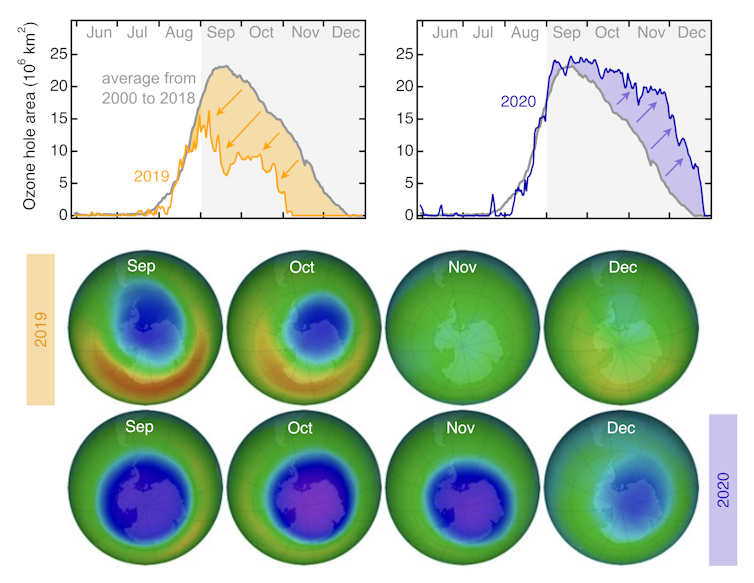

But over the past four years, even as the hole has shrunk, it has remained unusually long. Our new research revealed that instead of closing in November, it stayed open until December. It’s early summer—the critical period for new plant growth in coastal Antarctica and peak breeding season for penguins and seals.

This is a concern. When the ozone hole forms, more UV rays pass through the atmosphere. And while penguins and seals have protective coverings, their young may be more vulnerable.

Why is ozone important?

Over the past half century, we have damaged the Earth’s protective ozone layer by using chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and related chemicals. Thanks to coordinated global action, these chemicals are now banned.

Because CFCs are long-lived, it will take decades to be completely removed from the atmosphere. As a result, we still see ozone holes forming every year.

The lion’s share of ozone damage occurs over Antarctica. When the hole forms, the UV index doubles to extraordinary levels. We might expect to see UV days greater than 14 in summer in Australia or California, but not in polar regions.

Fortunately, on land, most species are protected under snow when the ozone hole opens in early spring (September to November). Marine life is protected by the sea ice cover and Antarctic moss forests are under the snow. These protective ice caps have helped protect most life in Antarctica from the depletion of the ozone layer—until now.

Ozone holes with unusual lifetimes

A series of unusual events between 2020 and 2023 caused the ozone hole to continue until December. A record-breaking 2019-2020 Australian bushfires, a massive underwater volcanic eruption in Tonga, and three straight years of La Nina.

Volcanoes and wildfires can inject ash and smoke into the stratosphere. Chemical reactions on the surface of these tiny particles can destroy ozone.

These longer-lived ozone holes coincided with a significant loss of sea ice, which meant many animals and plants had fewer places to hide.

(NASA Ozone Clock, CC BY-NC-ND)

What does stronger UV radiation do to ecosystems?

If the ozone holes persist, summer animals around the vast Antarctic coastline will be exposed to high levels of reflected UV radiation. More UV rays can get through, and ice and snow are highly reflective and bounce these rays around.

In humans, high UV exposure increases the risk of skin cancer and cataracts. But we don’t have fur and feathers. While penguins and seals have skin protection, their eyes are not.

Does it hurt? We don’t know for sure. Very few studies report on what UV radiation does to animals in Antarctica. Most of them are done in zoos, where researchers study what happens when animals are kept under artificial light.

However, this is a concern. More UV radiation in early summer can be especially harmful to young animals such as penguin chicks and seal pups that hatch or are born in late spring.

As plants such as Antarctic hair grass, Antarctic deschampsiacushion plant, Colobanthus comensis And many mosses emerge from the snow in late spring, exposed to maximum UV.

Antarctic mosses actually produce their own sunscreen to protect themselves from UV rays, but this comes at the cost of reduced growth.

Trillions of tiny phytoplankton live beneath the sea ice. These microscopic floating algae also make sunscreen compounds called microsporin amino acids.

What about sea creatures? If UV radiation is too high, krill sink deeper into the water column, while fish eggs usually contain melanin, the same protective compound as humans, although not all fish life stages are well protected.

Four out of the last five years have seen a decrease in sea ice extent, which is a direct consequence of climate change.

Less sea ice means more UV rays can penetrate the ocean, where it makes it harder for phytoplankton and Antarctic krill to survive. It mostly relies on these small organisms that form the base of the food web. If it is more difficult for them to survive, starvation will ripple up the food chain. Antarctic waters are also becoming warmer and more acidic due to climate change.

An uncertain outlook for Antarctica

We should rightly celebrate the success of the CFCS ban – a rare example of solving an environmental problem. But it may be premature. Climate change may delay the recovery of our ozone layer, for example, making wildfires more common and more severe.

Ozone may also suffer from geoengineering proposals such as sprinkling sulfates into the atmosphere to reflect sunlight, as well as frequent missile launches.

If the recent trend continues and the ozone hole continues into the summer, we can expect more damage to flora and fauna – which comes with other threats.

We don’t know if the ozone hole will last much longer. But we know that climate change is causing the atmosphere to behave in unprecedented ways. To keep ozone recovery on track, we need to take urgent action to reduce carbon emissions into the atmosphere. ![]()

Sharon Robinson, Distinguished Professor and Deputy Director of the ARC Securing the Antarctic Environmental Future (SAEF), University of Wollongong, University of Wollongong; Laura Rolle, Associate Professor of Environmental Physics, University of Canterbury, and Rachel Osola, Postdoctoral Fellow, Colorado State University

This article from The Conversation is republished under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

#expansion #Antarctic #ozone #hole #raised #concerns #penguin #seal #breeding