Sharks near the Gulf of Mexico are increasingly involved in destruction.

Shark conservation efforts have been so successful over the past two decades that researchers are testing ways to reduce human-shark conflict as populations continue to grow.

Sharks are increasingly becoming a nuisance to fishermen as they engage in predation — either attacking or robbing — the catch, said Demian Chapman, senior scientist and director of the Shark Research Center at Mott Marine Laboratory and Aquarium in Sarasota. .

Chapman told ABC News that a device the size of a quarter roll that shocks sharks that try to bite on fishing lines may be the answer to reducing shark kills as well as shark bycatch.

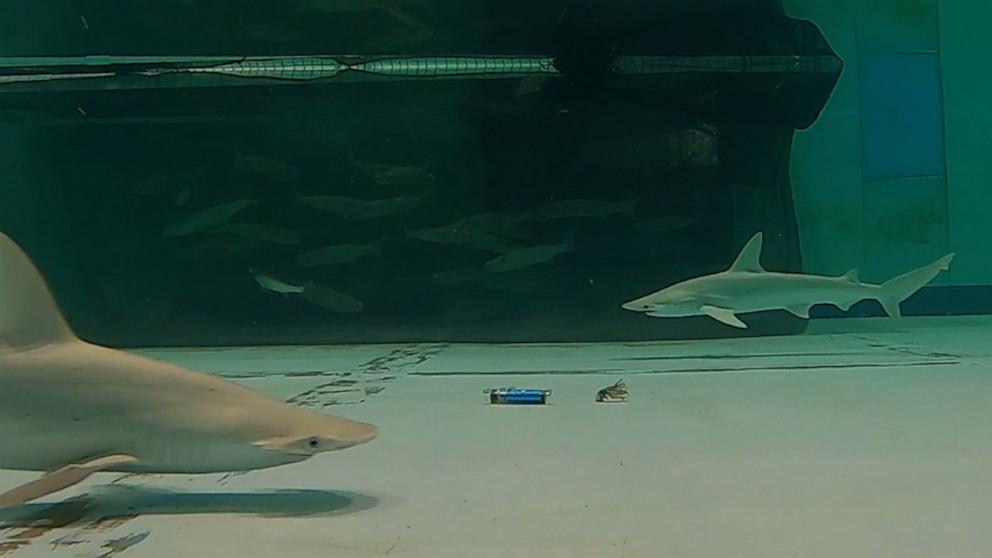

The SharkGuard electric pulse arrester attaches to the fishing line at the sink about 10 inches from the bait. The device sends out shock waves with the power of a quill pen that intensify the sharks’ sensitive pores to detect prey.

“That’s a feeling we don’t have,” Chapman said. “It doesn’t seem to hurt them, but they don’t enjoy the feeling.”

The device was developed by a UK-based company called Fishtec Marine, which published a paper in 2022 that showed promising results in reducing bycatch in the long-long tuna fishery.

Now, researchers at the Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium in Sarasota, Fla., conduct their experiments in a research lab equipped with tanks that can hold 60,000 gallons of water — a much cheaper process than running experiments in the field, Chapman said. .

When the device is placed in the tank, it both delays and deters the sharks from trying to grab the bait, Chapman said. After the initial shock, sharks sometimes won’t take the bait at all and become “wedges” at the bottom of the tank, Chapman said.

Experiments show that for sharks that try again, it takes more than twice as long to reach the bait.

Chapman said the delay could be beneficial to fishermen because they have more time to retrieve fish before the shark strikes again.

So far, researchers have tested small hammerhead and hammerhead sharks. But they’re looking to test a wider range of species, including sandbar sharks, which are known to steal fish, Chapman said.

According to a study published in Science in 2019, an estimated 100 million sharks are killed annually by humans. Many of these deaths are the result of bycatch of fish.

Management practices put in place over the past two decades have allowed shark populations to rebound, Chapman said.

Mote has been conducting shark surveys off the coast of Sarasota since 2003. Every three months, researchers go to the Gulf of Mexico to tag sharks to better understand population growth rates.

In 2021, researchers caught a record 104 sharks — eight different species — in four days, the most caught in a single summer season.

The number of sharks tagged per hour has been increasing over the past 20 years, but Chapman doesn’t describe the increase in numbers as an overpopulation or an influx.

“We don’t know if they’re at a level where they should be important to the ecosystem,” he said. But we know there are more of them and so we have to learn how to live with them again.”

#Shark #conservation #successful #researchers #finding #ways #curb #humanshark #interactions